Book of Exodus

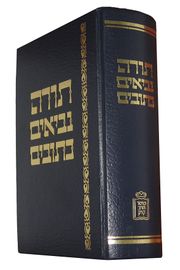

Exodus (Greek: ἔξοδος, exodos, meaning "departure") or Shmot (Hebrew: שמות, literally "names", Biblical Hebrew: Sh'moth) is the second book of the Hebrew Bible, and the second of five books of the Torah/Pentateuch.

Moses leads the Hebrews out of Egypt and through the wilderness to the Mountain of God: Mount Sinai. There Yahweh, through Moses, gives the Hebrews their laws and enters into a covenant with them, by which he will give them the land of Canaan in return for their faithfulness. The book ends with the construction of the Tabernacle.

According to tradition, Exodus and the other four books of the Torah were written by Moses. Modern biblical scholarship places its final textual form in the mid 5th century BCE, although a minority but important view would consider it a product of the Hellenistic period.[1]

Contents |

Title

In Hebrew the book is called Shemot, meaning "Names", from the second word of the Hebrew text, in line with the other four books of the Torah. When the Bible was translated into Greek in the 3rd century BCE to produce the Septuagint, the name given was Exodus (Greek: έξοδος, exodos) meaning "departure", in line with the Septuagint use of subject themes as book names. The Greek title has continued to be used in all subsequent Latin and English versions of the book, and most other languages.

Summary

|

Part of a series

of articles on the |

|---|

| Tanakh (Books common to all Christian and Judaic canons) |

| Genesis · Exodus · Leviticus · Numbers · Deuteronomy · Joshua · Judges · Ruth · 1–2 Samuel · 1–2 Kings · 1–2 Chronicles · Ezra (Esdras) · Nehemiah · Esther · Job · Psalms · Proverbs · Ecclesiastes · Song of Songs · Isaiah · Jeremiah · Lamentations · Ezekiel · Daniel · Minor prophets |

| Deuterocanon |

| Tobit · Judith · 1 Maccabees · 2 Maccabees · Wisdom (of Solomon) · Sirach · Baruch · Letter of Jeremiah · Additions to Daniel · Additions to Esther |

| Greek and Slavonic Orthodox canon |

| 1 Esdras · 3 Maccabees · Prayer of Manasseh · Psalm 151 |

| Georgian Orthodox canon |

| 4 Maccabees · 2 Esdras |

| Ethiopian Orthodox "narrow" canon |

| Apocalypse of Ezra · Jubilees · Enoch · 1–3 Meqabyan · 4 Baruch |

| Syriac Peshitta |

| Psalms 152–155 · 2 Baruch · Letter of Baruch |

|

|

Bondage in Egypt

Egypt's Pharaoh, fearful of the Israelites' numbers, orders that all newborn boys be thrown into the Nile. A Levite woman saves her baby by setting him adrift on the river in an ark of bulrushes. The pharaoh's daughter finds the child, and names him Moses, and brings him up as her own. But Moses is aware of his origins, and one day, when grown, kills an Egyptian overseer who is beating a Hebrew man, and has to flee into Midian.[2] There he marries the daughter of Jethro[3] the priest, and on Mount Horeb,[4] encounters God in a burning bush. God reveals his name, YHWH, to Moses, and tells him to return to Egypt and lead the Hebrews into Canaan, the land promised to Abraham.

Moses returns to Egypt, where God again says his name to Moses. God instructs Moses to appear before the pharaoh and inform him of God's demand that he let God's people go. Moses and his brother Aaron do so, but pharaoh refuses. God causes a series of ten plagues to strike Egypt, but whenever pharaoh begins to relent God, "Pharaoh's heart stiffened" (Exodus 7:13). God instructs Moses to institute the Passover sacrifice among the Israelites, and kills all the firstborn children and livestock throughout Egypt. The pharaoh then agrees to let the Israelites go. Moses explains the meaning of the Passover: it is for Israel's salvation from Egypt, so that the Israelites will not be required to sacrifice their own sons, but to redeem them.

Journey through the wilderness to Sinai

The Exodus begins. The Israelites, enumerated at 603,550 able-bodied adult males (not counting Levites) and their families, with their flocks and herds, set out for the mountain of God.[5] The pharaoh pursues them, and Yahweh destroys the Egyptian army at the crossing of the Red Sea (Yam Suf). The Israelites celebrate. The desert proves arduous, and the Israelites complain and long for Egypt, but God provides manna and miraculous water for them. The Israelites arrive at the mountain of God, where Moses' father-in-law Jethro visits Moses; at his suggestion Moses appoints judges over Israel.

At Sinai: Covenant and laws

The Israelites arrive at the mountain of God.[6] Yahweh asks whether they will agree to be his people, and they accept. The people gather at the foot of the mountain, and with thunder and lightning, fire and clouds of smoke, and the sound of trumpets, and the trembling of the mountain, God appears on the peak, and the people see the cloud and hear the "voice" of God [7] Moses and Aaron are told to ascend the mountain.[8] God pronounces the Ten Commandments (the Ethical Decalogue) in the hearing of all Israel.[9] Moses goes up the mountain into the presence of God, who pronounces the Covenant Code,[10] (a detailed code of ritual and civil law), and promises Canaan to the Hebrews if they obey.[11] Moses descends and writes down Yahweh's words and the people agree to keep them. Yahweh calls Moses up the mountain together with Aaron and the elders of Israel, and they feast in the presence of Yahweh. Yahweh calls Moses up the mountain to receive a set of stone tablets containing the law, and he and Joshua go up, leaving Aaron in charge. Yahweh appears on the mountain "like a consuming fire" and calls Moses to go up, and Moses goes up the mountain.[12]

Yahweh gives Moses instructions for the construction of the tabernacle so that God can dwell permanently amongst his chosen people, as well as instructions for the priestly vestments, the altar and its appurtenances, the ritual to be used to ordain the priests, and the daily sacrifices to be offered. Aaron is appointed as the first High Priest, and the priesthood is to be hereditary in his line. Yahweh gives to Moses the two stone tablets containing these instructions, written by God's own finger.

Aaron makes a golden calf, which the people worship. God informs Moses of their apostasy and threatens to kill them all, but relents when Moses pleads for them. Moses comes down from the mountain, smashes the tablets in anger, and commands the Levites to massacre the disobedient. Yahweh commands Moses to make two new tablets on which He will personally write the words that were on the first tablets. Moses ascends the mountain, God dictates the Ten Commandments (the Ritual Decalogue)[13], and Moses writes them on the tablets.[14]

Moses descends from the mountain, and his face is transformed, so that from that time onwards he has to hide his face with a veil. Moses assembles the Hebrews and repeats to them the commandments he has received from Yahweh, which are to keep the Sabbath and to construct the Tabernacle.[15]"And all the construction of the Tabernacle of the Tent of Meeting was finished, and the children of Israel did according to everything that Yahweh had commanded Moses",[16] and from that time Yahweh dwelt in the Tabernacle and ordered the travels of the Hebrews.[17]

Structure and composition

More than a century of archaeological research has discovered nothing which could support the narrative elements of the book of Exodus. The four centuries sojourn in Egypt, the escape of well over a million Israelites from the Delta, or the three months journey through the wilderness to Sinai.[18] The Egyptian records themselves have no mention of anything recorded in Exodus, the wilderness of the southern Sinai peninsula shows no traces of a mass-migration such as Exodus describes, and virtually all the place-names mentioned, including Goshen (the area within Egypt where the Israelites supposedly lived), the store-cities of Pithom and Rameses, the site of the crossing of the Red Sea (or, more commonly among modern Biblical scholars, the Sea of Reeds), and even Mt Sinai itself, have resisted identification.[19] Scholars who hold the Exodus to represent historical truth concede that the most the evidence can suggest is plausibility.[20]

For much of the 20th century the dominant theory on the origins of the book of Exodus was the documentary hypothesis; this held that the entire Torah was the result of the skillful interweaving of at least four originally independent and complete books dating from various points after 900 BCE, with the final redaction around the middle of the 1st millennium.[21] The documentary hypothesis no longer dominates biblical studies, but few doubt that the book is the product of many hands over many centuries.[1][22]

Equally unsettled is the question of the structure of Exodus - it has been divided by scholars into anywhere from two to five sections, all reflecting various aspects of the book's internal logic, but there is no single analysis which captures all the possible features that need to be taken into account.[23] Another consideration is the possibility that Exodus as we have it may simply be a by-product of the size of the scrolls used by the ancient scribes, since it was originally part of what was apparently conceived as part of the single narrative of the Torah. It is distinguished, however, from the preceding material in Genesis by the introduction of the figure of Moses and the escape-and-return theme, and from the following legal material in Leviticus by its nature as narrative.[24]

Themes

The central theme of Exodus is Israel's relationship with God: initiated by divine will (God initiates the action at each stage, from the Burning Bush to the epiphany at Sinai), it is to be maintained by their faithfulness to the covenant began with Noah and expanded with Abraham in Genesis, and now brought to a climax at Sinai.[25]

Exodus also shows the importance of genealogy in the Tanakh: Israel is elected for salvation because it is the firstborn son of the Lord, descended though Shem and Abraham to the chosen line of Israel/Jacob. (The theme of election by birth will later narrow still further, to the line of David, the descendant of Judah).[26]

The goal of the divine plan as revealed in Exodus is a return to man's state in Eden, so that the Lord could dwell with the Hebrews as he had with Adam and Eve: in Exodus, he dwells with Israel through the medium of the Ark and Tabernacle, which together form a model of the universe. Israel is thus the guardian and also the object of God's plan for mankind.[27] That so much of the book (chapters 25-31, 35-40) is spent describing the plans of the Tabernacle, demonstrates the importance it played in the life of the Hebrews. It was God's regular, permanent means of being with them, and gave them communion with him.[28]

See also

| Books of the Torah |

|---|

|

- The Exodus

- Moses

- Tabernacle

- Weekly Torah portions in Exodus: Shemot, Va'eira, Bo, Beshalach, Yitro, Mishpatim, Terumah, Tetzaveh, Ki Tisa, Vayakhel, and Pekudei

- Shovevim

- Film adaptations of the Book of Exodus

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rolf Rendtorff, "Directions in Pentateuchal Studies", CR:BS5 (1997), pp.43-65; and David M. Carr, "Controversy and Convergence in Recent Studies of the Formation of the Pentateuch", RSR23 (1997), pp.22-29

- ↑ Midian: the desert region around the head of the Gulf of Aqaba.

- ↑ Moses' father-in-law is named Reuel and Jethro in the Torah, and Hobeb in Judges. Hobeb also appears in the Torah (in Numbers), but is identified there as a son of Reuel.

- ↑ Horeb: the name given to the "mountain of God" named Sinai elsewhere

- ↑ Numbers 1:45, Exodus 38:26

- ↑ The arrival of the Israelites at Sinai is described twice.

- ↑ The Hebrew word beqol normally means voice, but a few verses earlier (Exodus 19:16) it has been used to mean "thunder", in the context of the thunder and lightning from the mountain. It is therefore not clear exactly what beqol means in this instance. The implication of Exodus 20:18-19 is that the people hear only thunder and trumpets and for this reason appoint Moses as their mediator with God: "And the people saw the thunder and the lightning and the sound of the trumpet and the mountain smoking...And they said [to Moses], "You speak with us, so we may listen, but let God not speak with us or we will die." Some translations therefore have "thunder" instead of "voice".

- ↑ It is not totally clear who goes up the mountain - Exodus 19:24 has Yahweh instructing Moses and Aaron to go up while the people and priests remain below, but at Exodus 19:22 the priests are told they may approach Yahweh after consecrating themselves.

- ↑ A slightly different version of the Commandments is given at Deuteronomy 5, the most striking variation being in the reason given for keeping the Sabbath: in Exodus, the Sabbath is kept because God made the heavens and earth in six days and rested on the seventh; in Deuteronomy, it is a memorial for Israel's deliverance from Egypt.

- ↑ Exodus21:1-23:19

- ↑ Exodus 21-23

- ↑ This passage has a confusing sequence of events, as reflected in this summary.

- ↑ The Ritual Decalogue, unlike the Ethical Decalogue, is explicitly called the "ten commandments" - see Exodus 34:28

- ↑ At Exodus 34:1 God has told Moses that he, God, will personally write on the tablets, but at Exodus 34:27 he tells Moses to write them. Also, although God tells Moses that he is about to receive a copy of the first set of tablets, Exodus 24:12 makes clear that the first tablets contained the instructions for the tabernacle, while Exodus 34:27-28 makes it equally clear that the second set contain the Ritual Decalogue.

- ↑ The detailed descriptions of the Tabernacle and related items take up chapters 25-31 and 35-40, or more than one fourth, of the Book of Exodus.

- ↑ Exodus 39:32

- ↑ This is a broad summary of the final verses, Exodus 40:34-38

- ↑ James Weinstein, "Exodus and the Archaeological Reality", in Exodus: The Egyptian Evidence, ed. Ernest S. Frerichs and Leonard H. Lesko (Eisenbrauns, 1997), p.87

- ↑ John Van Seters, "The Geography of the Exodus", in The Land I Will Show You: Essays on the History and Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Honour of J. Maxwell Miller, ed. J. Andrew Dearman and M. Patrick Graham (JSOT 343, Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), pp. 255-76

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, (OUP, 1999)

- ↑ Richard E. Friedman, The Bible With Sources Revealed, (HarperSanFrancisco, 2003), pp.1-31

- ↑ William H. Propp, Exodus 19-40, volume 2A of The Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday, 2006, ISBN 0-385-24693-5, Appendix A, pages 723-734

- ↑ William H. Propp, Exodus 1-18, volume 2 of The Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday, 1998, ISBN 0-385-14804-6, pp.37-8

- ↑ Menahem Haran, Book-Scrolls at the Beginning of the Second Temple Period: The Transition From Papyrus to Skins, (HUCA14, 1983), pp.11-22

- ↑ C. Marvin Pate, et al. The Story of Israel: a biblical theology (InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, 2004) pp 39.

- ↑ Stephen G. Dempster. Dominion and dynasty (InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, 2006) pp. 97-8.

- ↑ Stephen G. Dempster. Dominion and dynasty (InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, 2006) pp. 100.

- ↑ Stephen G. Dempster. Dominion and dynasty (InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, 2006) pp. 107.

External links

Online versions and translations of Exodus

Hebrew translations

- Exodus at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Exodus (The Living Torah) Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's translation and commentary at Ort.org

- Shemot - Exodus (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Shmot (Original Hebrew - English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

Gateway translations

| Preceded by Genesis |

Hebrew Bible | Followed by Leviticus |

| Christian Old Testament |